This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

July 2005 - Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Text and photos by Achim Schröer

The Alte Pinakothek (Old Gallery) in Munich is a product of two different periods in German history and architecture: the early nineteenth century and the post-war years of the twentieth century. It is the work of both Leo von Klenze (1784-1864) and Hans Döllgast (1891-1974). The sixtieth anniversary of the end of World War II is an appropriate occasion to highlight Döllgast’s “creative reconstruction” architecture, which made a unique contribution to the architectural discourse of post-war Germany.

Döllgast never made it to the top list of internationally known architects, but he was very influential in Bavaria due to his practical and academic work. He started his career as a modest modernist, working with Peter Behrens in Berlin and designing a 1920s housing estate in Munich-Neuhausen. He was also influenced, though, by ancient Roman architecture and Scandinavian modern classicism. In the 1930s he began to focus on church buildings and started teaching at Munich’s Technical University. He is best known for his post-war “creative reconstruction” works, of which the Alte Pinakothek is the masterpiece.

The first phase of the building, however, begins in the 1810s. The Kings of Bavaria, having gained greater power after the Napoleonic wars, had started a programme to transform Munich into a worthy royal capital. The so-called Maxvorstadt, a new suburb to the west of the old town and the palace, provided bourgeois housing and space for representative layouts and buildings. King Ludwig I commissioned Leo von Klenze, Bavaria’s most distinguished classical architect, with a new building for the growing royal art collections. Built 1826-1836 in a neo-renaissance style, the Alte Pinakothek block stretches generously in an east-west direction. Making skilful use of northern and top light, the building was the most modern purpose-built gallery of its time; some rooms take their proportions directly from the featured paintings. Together with the museums around Klenze’s classical Königsplatz and the later Neue Pinakothek nearby, it became part of a museums’ quarter of European importance (recently extended by the “Pinakothek der Moderne” just next to it).

In the next 100 years the Maxvorstadt turned into a lively inner-city area, hosting Munich’s two universities. The Nazis also shaped the area with the NSDAP’s headquarters close to Königsplatz. From 1942 onwards, the bomb war (originally a Nazi invention) turned back on Germany and Munich, and the Maxvorstadt was one of the most affected areas. The collection of the Alte Pinakothek had been secured, but one third of the building was completely destroyed, and the rest had been burned out.

After the war, German architects faced a unique situation. The task of providing lots of buildings was overlaid by the question of how one should deal with the immediate past and the destruction of German cities; psychologically we might even say: how one should deal with guilt. The positions ranged from detailed restoration and re-building of what had been destroyed, in order to keep Germany’s cultural heritage but often accused of being an attempt to repress the catastrophe of the war; to reconstruction in simplified, “modernised” forms; and eventually to new development in modernist styles, marking the alleged beginning of a new period, which was just another form of repression. In the end, the reconstruction of German cities happened in many ways, and step-by-step the traces of war were removed.

In this context, Döllgast found his own approach with his so-called “creative reconstruction” method, which took account of the whole history of a building, and therefore of its destruction and reconstruction. The remains of a building were kept, but re-interpreted. Missing parts were not imitated but added in a modern way, often using the rubble bricks of destroyed buildings. On the one hand these bricks, in an old Bavarian size, were a material that Döllgast was very fond of, on the other hand their origin, as rubble from the bomb raids, added a peculiar symbolic value. Nowadays, decades after the Venice charter, we may have got used to the contrast of the “old and simplified new” look, but in the immediate post-war context, his solution was groundbreaking. Other examples of his work are the church of St. Bonifaz and some cemetery buildings in Munich.

As early as 1946 and without a brief, Döllgast devised concepts for a reconstruction of the Alte Pinakothek. But other architects pleaded for a demolition of the ruins and for a new building, and so it took Döllgast six years of campaigning and many varied designs to get a brief from the government. An important argument was that his concept was far cheaper than any new building.

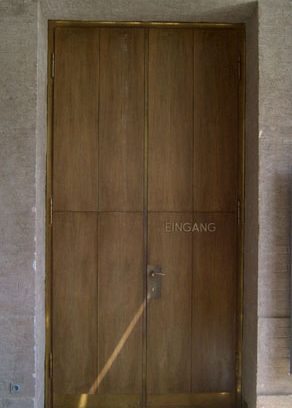

Döllgast’s preference for simple solutions perfectly met his goal of integrating the building’s history. He left most of the damage visible, foremost the bomb crater at the centre of the building, which he filled with a construction made of rubble bricks from the Pinakothek itself and from neighbouring military barracks. But he went far beyond a conservationist’s approach, changing the whole layout of the building. Klenze’s Pinakothek, having the entrance and the staircase in the eastern wing of the building, had featured a long loggia behind the south façade. Döllgast moved the entrance to the centre, on the building’s northern façade, and used the former loggia’s void for a monumental staircase (which also met new safety regulations). Together with the plain brickwork of the interior, an archaic and almost sacred space was created, which resembles the modern classicist architecture of Asplund. Unfortunately, he could not maintain this approach in the exhibition rooms, which are a very simplified version of the plastered pre-war rooms. The Alte Pinakothek was re-opened in 1957.

Due to the building’s provisional character, the “complete restoration” of Klenze’s Pinakothek was often demanded. Fortunately, this was refused during the minor renovations of the 1960s and the 1990s, and so the Alte Pinakothek survives as a unique testimony to wartime destruction and post-war reconstruction in Munich.

The Alte Pinakothek is one of Munich’s major museums and features European masters from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century, based on the former royal collections. The Museum can be found at: Alte Pinakothek, Barer Straße 27, Entrance from Theresienstraße, München. It is o pen daily, except Monday, from 10.00-17.00, on Tuesday from 10.00-20.00 www.alte-pinakothek.de

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.